How dental preventative products have changed over time

From brushing to flossing, rinses to mouthwash, preventative products have enjoyed drastic improvements over the years.

Throughout history, people have gone to extreme lengths in the name of oral hygiene. At one point, toothpaste contained hydrochloric acid, expensive toothbrushes were carved out of bone, and bristles were made from pig hair. People have flossed with silk, swished with beer, and worst of all, used bottled urine as a mouthwash. The history of oral care is expansive and, yes, sometimes off-putting, but no less fascinating.

Toothbrushes

Starting with the Babylonians around 3500 BC, oral care was a priority for humans with the discovery of early toothbrushes.1 Chewing sticks, called miswak or siwak, were used as toothbrushes either alone or with tooth powder or extract of roses.1

Toothbrushes didn’t get bristles for about 5,000 years. The earliest known written reference describing a toothbrush (a long narrow handle with bristles standing at right angles on one end) was discovered in a Chinese encyclopedia from the 17th century, which noted that the Chinese toothbrush was invented in 1498.2 Toothbrushes showed up in Europe in the 17th century, and in the US starting in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.2 H.N. Wadsworth received the first patent in 1857, but toothbrushes were challenging to mass produce because the hog bristles used for the brush were expensive.1

The Natural Museum of American History has a collection of early toothbrushes from the United States, the earliest ones had bone or ivory handles with pig bristles inset on the large heads, and brand names inscribed on the handles.3 Early toothbrushes could often fold in half, or have a handle that also served as a case for the brush.3 Later, in the 1930s, hog bristles were replaced with nylon and the handles switched to Bakelite, celluloid, or other plastics. They were sold inside glass or plastic packaging to keep them sanitary.3

The 1930s also produced the first electric toothbrush, but it wasn’t widely used. It was invented in 1939 in Scotland, but electric toothbrushes weren’t marketed to the public until the 1960s.1 The first commercial electric toothbrushes were developed in Switzerland and were followed the next year, in 1961 with a rechargeable model.4

Floss

The first mentions of concern about the interproximal cleaning challenges of teeth appeared in the 19th century.1 Dr. Levi Spear Parmly introduced flossing as the most efficient way to prevent disease and actually invented dental floss made of silk.1 In 1882, Massachusetts-based Codman and Shurtleff Company began making unwaxed silk floss.5 Sixteen years later, Johnson & Johnson began marketing floss as well, followed by a patent in 1898 on a floss made from a silk material used by doctors for stitches.5

It wasn’t until after World War II that manufacturers made floss out of nylon, which was an improvement as it resisted shredding and had a more consistent texture than silk. But perhaps most importantly, nylon could be waxed, which made it easier to use.5

Today’s floss uses a variety of different materials, including nylon, Teflon, and Gore-Tex. Eco-friendly versions are made from silk coated in beeswax or other plant-based wax. There are also different textures of floss and instruments designed to make it easier to floss around orthodontic or other dental appliances.5

Oral Hygiene

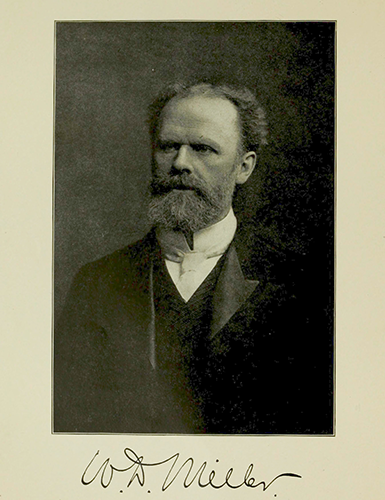

American dentist Willoughby Dayton Miller formulated the chemo-parasitic theory of caries in 1890.

It was not until 1890 that dentistry first discovered the connection between micro-organisms in the mouth and tooth decay.4 American dentist Willoughby Dayton Miller noted the link in his book Micro-Organisms of the Human Mouth. This revelation led to a new interest in oral hygiene and began a global movement to encourage people to improve oral health by brushing and flossing regularly.1

The emphasis on oral hygiene continued into the early twentieth century. Before then, dentistry was mostly focused on cleaning (with a cloth and an abrasive powder). Extractions were performed without local anesthetics, sometimes by a doctor, but other times by an apothecary, a barber-surgeon, or blacksmith.6 Anesthetics were sometimes used but were usually opium, nitrous oxide, ether, or cocaine, and sometimes, the patient only got a swig of whiskey beforehand.6 The movement began in schools as an education program. Dentists said that poor dental hygiene contributed to other diseases that kept people out of work and school.3 During the 1910s and 1920s, employers sometimes contracted dentists to care for factory workers’ teeth with examinations and cleanings. It’s thought that their motivations were less humanitarian-focused, and more financially-driven-by providing this service, fewer employees would miss work because of a tooth infection.3

Around this time, the first oral hygiene school for dental hygienists opened in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Founded in 1913 by the “Father of Dental Hygiene” Alfred C. Fones, the Fones Clinic for Dental Hygienists trained women who mostly started working for the Bridgeport Board of Education to clean student’s teeth. The children had fewer caries than previously, which further supported the dental hygiene movement. In 1917, Irene Newman earned the first dental hygiene license in the world.4

Despite these early movements to improve oral hygiene, it wasn’t until after World War II that regular attention to oral care became more widespread in the US. Returning soldiers, who brushed their teeth in the service as part of their daily hygiene routine, continued the practice when they returned from the war.4 Also, in 1945, the cities of Newburgh, New York, and Grand Rapids, Michigan begin adding sodium fluoride to public water systems.4 Over 200 million people, or 74 percent of the US population with community water, had access to fluoridated water by 2016. Furthermore, the reduction in caries that have resulted makes water fluoridation one of the top ten public health achievements of the 20th century.7

Tooth Polishing

Polishing the teeth to remove soft deposits and stains has been around for centuries, although it existed in a different form. Early Roman and Greek writings mention tooth polishing, but it wasn’t until Pierre Fauchard recommended polishing in the 17th century did the practice begin making regular appearances in history.8 Fauchard recommended polishing teeth with ground coral, egg, shells, ginger, or salt. When Fones founded the Dental Hygiene School over 200 years later, he trained students to polish teeth. However, it was not for health reasons at the time but instead for esthetics, and so it was a selective process.8

Eventually, dental professionals agreed that polishing the teeth would create smoother surfaces that didn’t allow the biofilm to accumulate. For much of the 20th century, up until the 1970s, patients considered tooth polishing part of the hygiene appointment. However, recent studies have moved away from this idea, and instead, support the selective polishing of patients’ teeth based on individual needs.8

Toothpaste

Like toothbrushes, toothpaste has early origins in human history. The earliest text on medicine from Egypt, the Ebers Papyrus dating to 4000 BC, has recipes for toothpaste, and the works of Hippocrates in the 4th and 5th centuries do as well.2

In more recent history, toothpaste was either a powder of cream crafted by local dentists and apothecaries. Called dentifrices, these kinds of toothpaste used common ingredients, like orris root, powdered cuttlebone, baking soda, chalk, and charcoal.3 Sometimes phenol or camphor was added for antiseptic purposes, and herbs such as peppermint or clove were added for taste.

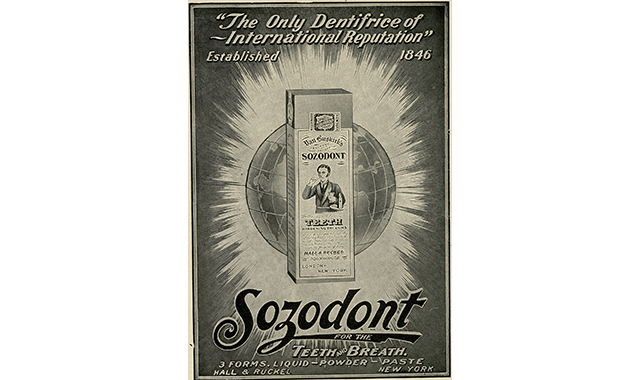

A Sozodont advertisement circa 1900. (Image credit: National Museum of American History)

However, at that time, there was not much oversight in these mixing processes. By the late 19th century, the most popular patented dentifrice, Sozodont contained 37.15 percent alcohol, a percentage so high, the manufacturer had to appear before Congress and testify that the product’s ingredients weren’t a way to buy liquor tax-free. Moreover, the Sozodont formula had ingredients that were abrasive and acidic enough that they gradually destroyed the users’ enamel. Later, in the 1930s, the ADA exposed the danger of three products-Ex-Cel Tooth Stain Remover, Bleachodent, and Snowy White, which contained hydrochloric acid. Another product in 1928 called Tartaroff dissolved three percent of the user’s enamel every time they used it.3

Toothpaste originally came in pots that users dipped their brushes in before brushing. However, a dentist in New London, Connecticut, was the first in the US to put it in a tube in 1890. Dr. Washington Wentworth Sheffield sold his Sheffield Crème Dentifrice in a collapsible tube, and it soon caught on across the market.2 By 1910, when mass marketing of toothpaste was more widespread, the collapsible metal tube became the usual packaging for toothpaste.4

Marketing oral care products changed around the 1940s. Toothpaste became more popular than powders and had a share of 75 percent of the market by 1949.3 The toothpaste marketing moved away from the cosmetic benefits to the oral health care benefits of destroying acid-producing bacteria that leads to tooth decay. However, the use of unique ingredients continued, with some toothpaste manufacturers adding ammonia, chlorophyll, and penicillin to prevent decay and bad breath.3

By 1950, the first fluoride toothpaste hit the market.4 When Crest introduced toothpaste with fluoride in 1955, the ADA recommended fluoride as the accepted additive to prevent tooth decay.3

Sealants

Once dentistry had established conventional ways to avoid dental caries (e.g., regular brushing and flossing, fluoride treatments, dietary changes, and routine office visits), some types of caries decreased. However, the pits and fissures of teeth remained an area that was prone to caries. Pit and fissure caries represent 90 percent of cavities in permanent posterior teeth and 44 percent of those in primary teeth for children and adolescents.9

Early in dentistry, there were different ways dentists tried to protect the pits and fissures of teeth from caries. Enamel fissure eradication involved widening the fissure to make them easier to clean. Some dentists treated the crevices with ammoniacal silver nitrate, which did not work.9 In 1923, H. T. Hyatt introduced a new technique called prophylactic odontotomy, a more invasive treatment than previous methods that involved widening the grooves with a shaping tip and then placing a prophylactic restoration.10 This method was used for several decades after Hyatt introduced it.

Sealants had their breakthrough as a treatment for pit and fissure caries in the 1950s. Dr. Michael G. Buonocore’s 1955 study documenting the discovery of bonding acrylic resin to etched enamel served to transform dental clinical practice and set the stage for dental sealants for preventative dentistry. The first sealant material, methyl cyanoacrylate, came out in the mid-1960s but wasn’t marketed for widespread use because it disintegrated in the mouth over time. Buonocore introduced BIS-GMA (bisphenol-a-glycidyl methacrylate) in 1970 as a pit and fissure sealant. Sealants became more common as a preventative method for protecting these vulnerable and hard to clean areas of the tooth.9

However, it wasn’t until 1983, when the National Institutes of Health (NIH) published a report that recommended the use of pit and fissure sealants as an effective way to prevent caries, that many states cleared the way for dental auxiliaries to place pit and fissure sealants. Moreover, the report convinced dental insurance that sealants were a cost-effective prevention method instead of an “experimental procedure.”10

Mouthwash

The earliest record of mouthwash use was in China in 2700 BC.1 About 2701 years later, Romans were buying bottled Portuguese urine to rinse out their mouths, taking advantage of the ammonia present for its disinfection and whitening properties.11 Surprisingly, urine remained an ingredient in mouth rinses until the 19th century.11 Romans later swished with tortoise blood to prevent toothaches, and to improve breath, they used goats’ milk and white wine beginning around AD 23.11 In AD 40-90, Greeks had a different formula for successful mouth rinsing. The Greek surgeon and physician Pedanius Dioscorides used olive juice, milk, gum myrrh, pomegranate, vinegar, and wine to fight halitosis.11 Through the years, the ingredients for mouthwash changed from pure cold water in the 1200s, to wine and beer in the 1500s, and to mint and vinegar in the 1600s.

Colgate's Antiseptic Dental Powder circa 1873. (Image credit: National Museum of American History)

Mouthwash as we know it has its origins in the late 19th century. Once Louis Pasteur published his theory about germs in 1860, an English physician, Dr. Joseph Lister explored how sterilization of the room could improve mortality rates during surgery and he was successful in reducing mortalities in 1865.12 Eleven years later, Dr. Lister recognized the work of an inventive duo, Dr. Joseph Lawrence and Robert Wood Johnson, founders of Johnson & Johnson. In 1879, Drs. Lawrence and Johnson named their new antiseptic product for surgery and wound cleaning Listerine in Dr. Lister’s honor. It wasn’t until 1895 that scientists discovered that Listerine was effective at killing germs in the mouth.12

Today, mouthwash has a variety of applications, other than freshening breath. Some mouthwashes have stain lifting qualities to help whiten teeth, while others have fluoride to help restore enamel. Many types of mouthwashes help control plaque, gingivitis, and dental caries, as well.

The surprising, and often strange, history of dental preventative products covers thousands of years and several continents. The products of today would be barely recognizable in ancient Greece or Rome. Thanks to new science and new innovations, we can brush our teeth worry-free.

References

- Jardim JJ, Alves LS, Maltz M. The history and global market of oral home-care products. Brazilian Oral Research. https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1806-83242009000500004. Published June 2009. Accessed June 4, 2020.

- FAQs on the History of Dentistry. Ada.org. https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Education%20and%20Careers/Files/faq_dentistry.pdf?la=en. Published 2020. Accessed June 4, 2020.

- Oral Care. Smithsonian Institution. https://www.si.edu/spotlight/health-hygiene-and-beauty/oral-care. Published 2020. Accessed June 4, 2020.

- History of Dentisty. Ada.org. https://www.ada.org/en/member-center/ada-library/dental-history. Published 2020. Accessed June 4, 2020.

- The History of Dental Floss. Oral-B. https://oralb.com/en-us/oral-health/dental-floss-history. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- Dentistry Has Changed. Smileguide.com. https://www.smileguide.com/dentistry-has-changed. Published 2020. Accessed June 4, 2020.

- Community Water Fluoridation. cdc.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/fluoridation/basics/index.htm. Published 2020. Accessed June 4, 2020.

- Sawai M, Bhardwaj A, Jafri Z, Sultan N, Daing A. Tooth polishing: The current status. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2015;19(4):375. doi:10.4103/0972-124x.154170

- Naaman R, El-Housseiny AA, Alamoudi N. The Use of Pit and Fissure Sealants-A Literature Review. Dent J (Basel). 2017;5(4):34. Published 2017 Dec 11. doi:10.3390/dj5040034

- Pit & Fissure Sealants: The Added Link in Preventative Dentistry. dentalcare.com. https://www.dentalcare.com/en-us/professional-education/ce-courses/ce128/history-sealant-use. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- Prichard D. A Brief History of Mouthwash. speareducation.com. https://www.speareducation.com/spear-review/2012/12/a-brief-history-of-mouthwash. Published 2012. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- History of Listerine Mouthwash. listerine.com. https://www.listerine.com/about. Published 2020. Accessed June 5, 2020.